Based on geological, ecological (flora and fauna), and archaeological evidence found on the Palaeoindian sites in the Eastern Townships, it is possible to formulate a hypothesis on the history of the first people to arrive in the region. To fit this bit of history into that of the settlement of North America, it is important to take into account other evidence found on the continent. The hypothesis presented below is generally accepted by the scientific community. It is separated into 5 sections.

1. Arrival in North America and the Beringia

2. Human dispersal in North America

3. Inhabitation of the Eastern Townships at the dawn of the Palaeoindian era

4. Arrival in the Eastern Townships

5. The second wave of migrants

In conclusion, this hypothesis raises questions still unanswered.

Beringia Land Bridge during the Last Glacial Maximum. Location of the Bluefish Caves and the Little John site in the Yukon.

Arrival in North America and the Beringia legend

The first humans arrived via Beringia, a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska. The era in which they arrived is still a hot debate among the scientific community. There are two opposing views: Those believing in a brief chronology, rejecting any date earlier than 15 000 years ago, and those believing in a long chronology based on earlier dates, such as those from the fossilized bones of wildlife in the Bluefish Caves in the Yukon. Radiocarbon dating results indicate that the oldest date back to 25 000 BP. Some of these fossilized bones bear marks that seem to indicate that they were carved by humans. However, this hypothesis is challenged by numerous archaeologists. They argue that these marks could have been caused by large carnivores or natural phenomena. According to other scientists, these results support the hypothesis of an isolated human population that persisted in Beringia during the Last Glacial Maximum and spread towards North and South America when the glaciers retreated. Furthermore, the stone tools found beside these fossilized bones date back about 14 000 years according to the typology. The Little John site near Beaver Creek in the Yukon is about the same age.

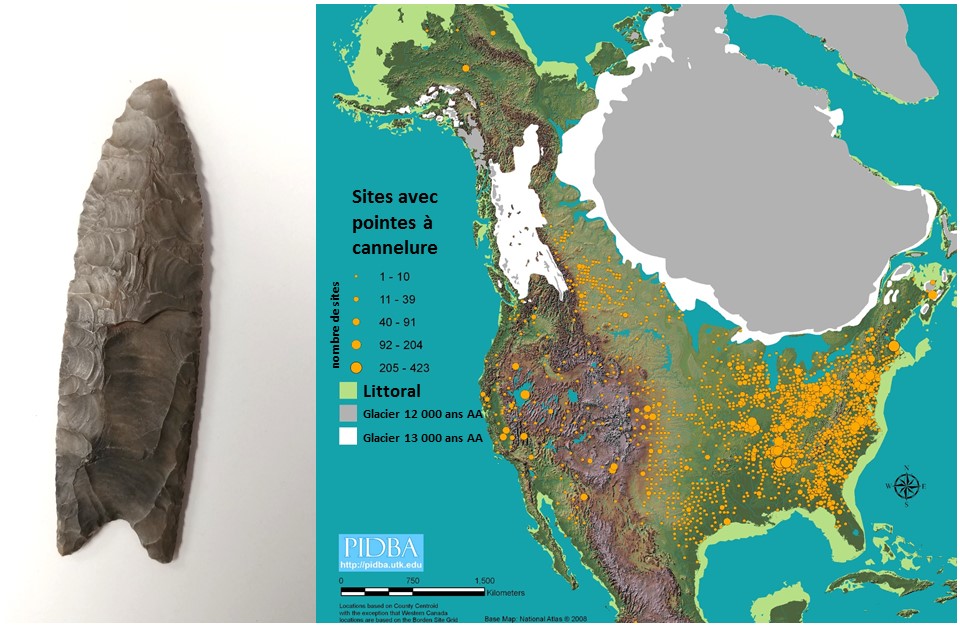

Clovis fluted point and map produced by the Paleoindian Database of the Americas (PIDBA), indicating the locations in North America where fluted points have been found.

Human dispersal in North America

The retreat of the glaciers gradually opened pathways to the south. It is believed that some 14 000 years ago, humans from Beringia crossed between the glacier and the coastline to populate the western plains south of the ice sheet. Starting 13 500 years ago, their descendants would have dispersed quickly throughout North America. These first Palaeoindians are called Clovis, from the name of the town where the first fluted point was discovered. They began a great migration south as far as Costa Rica, southeast to Florida, and east to Nova Scotia. More than 10 000 Clovis points (or their regional equivalents) have been found, in about 1 500 locations in North America. However, there is no trace of such points in collections of artifacts from Siberia. Clovis points seem to be a North American invention, perhaps even its first!

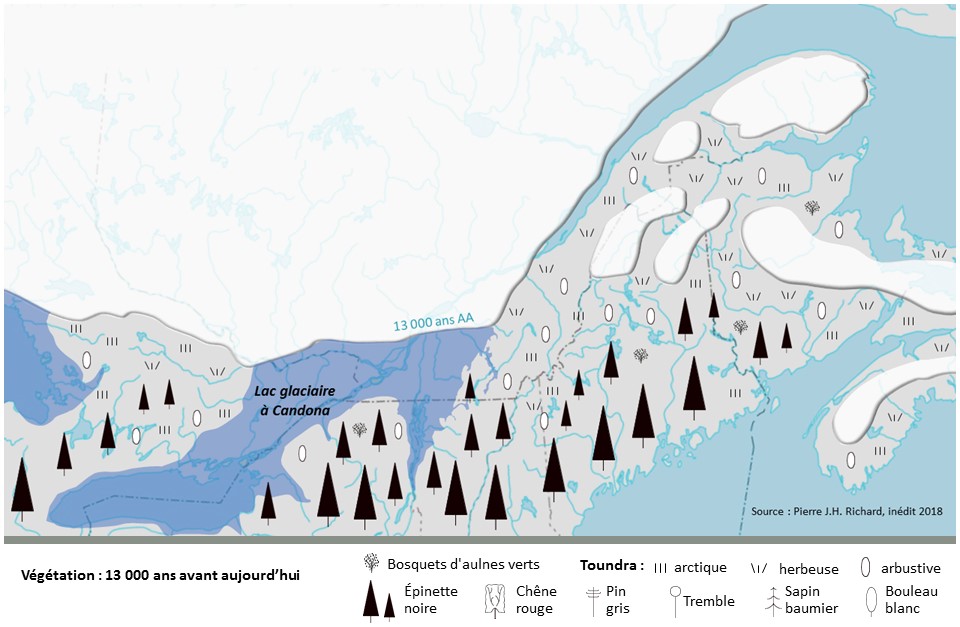

Geography of eastern North America at the dawn of the Palaeoindian period, 13 000 years ago. Ice melt created Lake Candona.

Inhabitation of the Eastern Townships at the dawn of the Paleoindian era

13 000 years ago, there were some Clovis descendants around the Great Lakes and they were advancing eastward. They went south beyond the gigantic Glacial Lake Candona and travelled through the spruce forests to reach the shores of the Atlantic Ocean 500 years later. In the Eastern Townships, the proximity of the ice sheet and the remaining residual glaciers in Maine, the Gaspésie, and the Maritimes caused harsh conditions suitable for sustaining tundra. The study of sediment cores has indicated the presence of grasses and dwarf shrubs that today characterize Arctic zones.

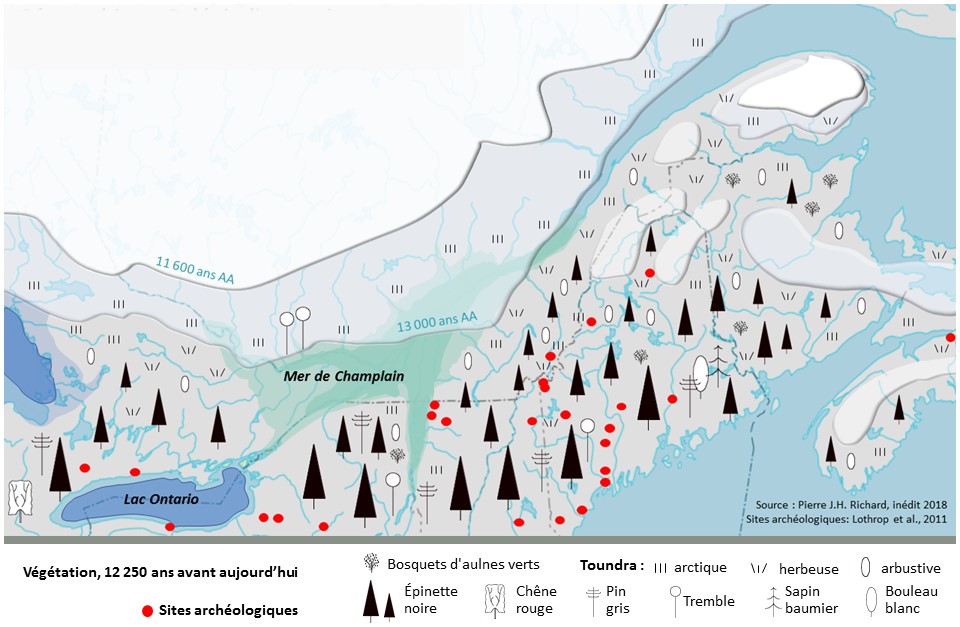

The environment during the Early Palaeoindian period (13 000 to 11 600 years BP) and archaeological sites from this period. The retreat of the glaciers led to the emptying of Lake Candona and the creation of the Champlain Sea.

Arrival in the Eastern Townships

During the summer, a number of Palaeoindians from New England headed north to intercept the caribou herds. This was the start of the settlement of the Eastern Townships. The Palaeoindians followed the Kennebec River, crossed the border mountains, and settled near Lake Megantic, one of the first locations in Quebec to be freed from the ice. The archaeological material discovered on the Cliche-Rancourt site in the Megantic region has strong similarities with assemblages from New England, in terms of both shapes and materials.

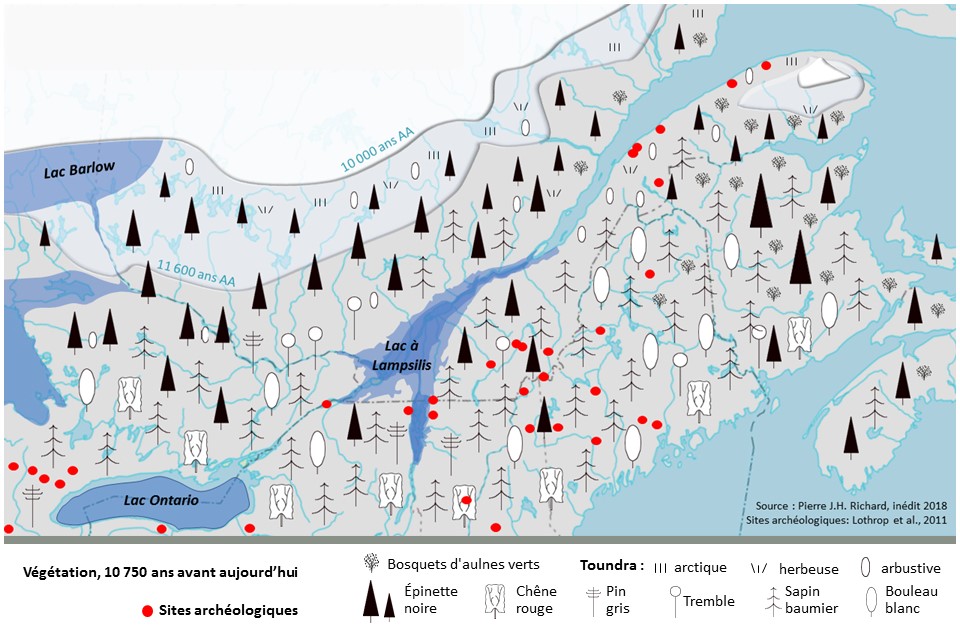

The environment during the Late Palaeoindian period (11 600 to 10 000 years BP) and archaeological sites from this period.

A second wave of migrants

About 11 700 years ago, the climate began to warm up again and deglaciation progressed. The retreat of the ice and the emptying of glacial lakes opened new pathways to the Eastern Townships. Consequently, a second wave of nomads arrived after travelling along the Great Lakes. Their points are associated with the eastern Plano culture, and plain hunters who had to adapt to an increasingly forested environment. Traces of them have been found on the four Palaeoindian archaeological sites in the Eastern Townships, particularly at the Kruger 2 site in Sherbrooke. The presence of firestone and a heated rhyolite biface at this site made it possible to use optically stimulated luminescence for dating. Therefore, the area was inhabited about 10 000 years ago.

On the left are Agate Basin points and on the right Ste. Anne-Varney point, both types found at the Kruger 2 site in Sherbrooke.

Unanswered questions

The Kruger 2 site contains several types of points from the Late Palaeoindian period chipped from different raw materials. There are two main models: Agate Basin points, deemed as older in the West, and Ste. Anne-Varney points, deemed as more recent. In the Estrie region, the issue of their relative age has been raised, especially as the soil has been disturbed and the stratigraphy is not conducive to establishing a solid relative chronology. Is the presence of two models made of the same materials indicative of two distinct groups in terms of time line, or of a single group crafting the two models for different uses during the same occupancy? For example, the Ste. Anne-Varney point could have been used with a thruster to hunt, while the wider and thicker Agate Basin points would have been used like a spear. The debate is still on!